The Soul of Photography: Unveiling the Essence of Analog

In an era of digital dominance, this piece explores the time-bound soul of analog photography, revealing its profound connection to materiality and spirit.

In a digital-drenched world, analog photography stands as a poignant reminder of how temporality is inherently tied to material constraints. Time, in its enigmatic essence, chronically and eternally alters everything. It is a force both primitive and potent, certain in its impact yet elusive in measurement. Photographic film, with its mineral composition, embodies this tangible finitude. It is more than a mere medium for capturing images; it is an artifact laden with the weight of time.

The chemical and mineral composition of photographic film provides a rich canvas for artistic exploration. Each grain of the image, each alteration from light exposure or chemical interaction, speaks to the relentless march of time. In creating a material constraint, we anchor temporality within a medium, marrying the intangible with the tangible, the genesis of meaning-making. To infuse meaning is to spiritualize matter. This fundamental feminine energy, the spiritualization of matter, resonates with the primitive masculine force of materializing the spirit.

The Film as a Symbol of Temporality

Photographic film is a complex weave of chemistry and mineralogy. Its essence lies in silver halide crystals, often embedded in gelatin, reacting to light. These crystals form the foundation of black and white imagery; their size and shape influencing the film's resolution and sensitivity. In color films, additional layers with organic compounds, sensitive to various light wavelengths, are added for color capture.

Light interacting with these crystals initiates a chemical transformation. Exposure to light turns silver halides into metallic silver, manifesting a latent image that only reveals itself post-development. This process involves other chemical agents, like the developer transforming ionized silver into metallic silver, and the fixer, erasing unexposed silver halide.

Each step in this process serves as a reminder of finitude. The finite availability of silver halide, the inevitable degradation of chemical compounds, and the physical deterioration of the film itself, all testify to the presence of temporality. Thus, every image becomes a unique outcome of a series of chemical and physical events, irrevocable and distinct, creating a singularity, an identity, a signature.

Historical Perspective and Current Situation on Silver Halide Crystal Extraction

The extraction and procurement of silver halide crystals, crucial for analog photography, typically start in mines where silver is extracted as ore. In 2023, a significant increase in global silver reserves and production was noted, with Mexico leading in production and China reporting the largest reserve increase. Other key countries in this domain include Peru, Australia, and Russia.

Most silver used for these crystals comes from secondary production during base metal extraction like zinc, lead, and copper, accounting for approximately 59% of global silver production. This secondary production is vital, as silver halide crystals are manufactured by combining extracted silver with halogens such as chlorine, bromide, or iodide.

With the decline in silver demand for analog photography following the rise of digital photography, a recent resurgence in interest for analog photography has been observed, potentially influencing future demand for these crystals. Additionally, growing interest in technologies like electric vehicles, 5G, solar panels, and green energy has spurred silver demand, with a reported demand of 1.1 billion ounces in 2022.

Nevertheless, silver reserves might be depleted in about 20 years, considering the current average lifespan of a silver mine is only about 10 years. This prospect raises significant ecological concerns, as silver extraction and processing to obtain silver halide crystals have considerable environmental impacts. These include soil and water pollution, natural habitat destruction, greenhouse gas emissions, and risks associated with chemical use. Therefore, it is crucial to strike a balance between the needs of analog photography and environmental concerns, to minimize impacts on natural resources and the environment.

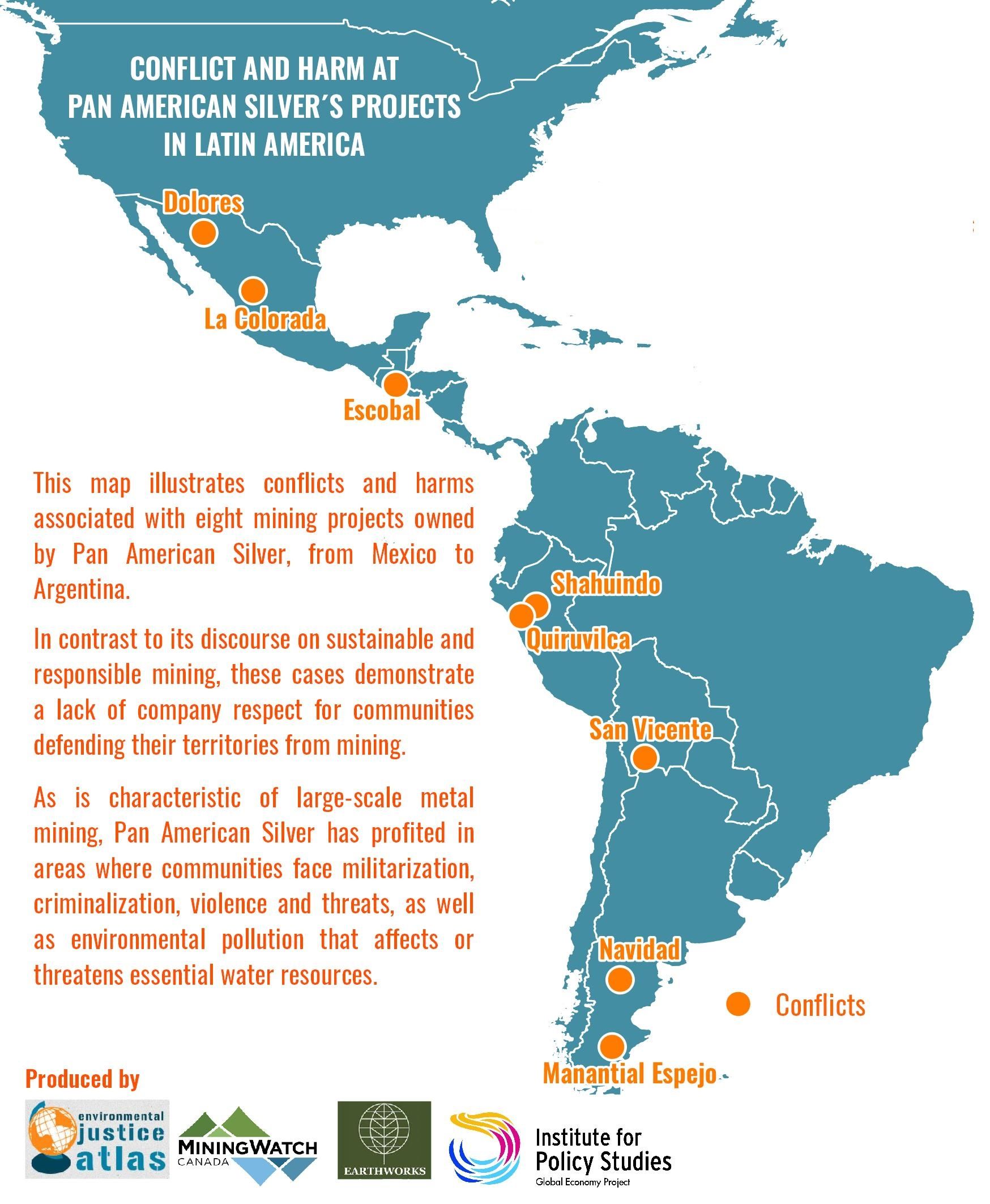

Environmental and Social Impacts: The Case of Pan American Silver Company

Pan American Silver (PAS, 2022 Revenue: 1.5 billion USD) is a Canadian mining company distinguished by its involvement in various projects across Latin America, spanning from Mexico to Argentina. Throughout this journey, PAS has found itself at the heart of environmental and social conflicts, where militarization, criminalization, violence, harassment, and threats often marked surrounding communities. More profoundly, environmental pollution, especially affecting vital water sources, has been a constant concern in its mines, illustrating the complexity and challenges of the modern mining industry.

In the shadow of the Peruvian Andes, the Shahuindo mine, operated by the Canadian company Pan American Silver, stands as a symbol of the dualities that traverse our era: progress and preservation, wealth and responsibility. Opened in 2016, this open-pit mine is an industry titan, designed to extract and process oxidized and mixed ores, with an estimated gold production of 10,000 tons per day and reserves amounting to 37.85 million tons. Yet, within the Condebamba Valley, this industrial giant is seen under a different light: as an invader altering the clear waters that have nourished these agricultural lands for generations.

Reports of heavy metal contamination since 2016 have aroused deep concern among residents, turning life-sustaining water into a vector of uncertainty. PAS's response has been swift: community projects, such as increasing avocado production and a guinea pig breeding program, aim to strengthen ties with these communities, offering training and funding in hopes of weaving a fabric of sustainable development and trust.

Far away, in Mexico, similar stories unfold. The La Colorada mine saw the local community displaced, a painful uprooting to make way for mining expansion. In Dolores, tension is palpable, exacerbated by military presence and territorial conflicts, painting a complex picture of the human and environmental impact of mining.

The Navidad project in Argentina, acquired by PAS in 2009, stands as a bastion against local opposition and regional laws, demonstrating the resilience of communities in their fight to preserve their land and way of life against open-pit exploitation and cyanide use.

But it is in Guatemala where the mosaic of challenges and hopes of PAS takes a particular color. With the acquisition of the Escobal mine, the Xinka people, guardians of a rich and deeply rooted culture, rose up. Non-Maya, this indigenous people have a distinct history, woven into the cultural fabric of Mesoamerica, and their communities, mainly located in the southern part of Guatemala, reflect a cultural diversity often unrecognized. Even before the arrival of the Mayas and Pipil, the Xinkas, present since the 12th century, occupied the Guatemalan Pacific plain, a testament to their ancestral presence and resilience through the centuries.

Faced with the exploitation of the Escobal mine, their peaceful resistance, marked by dignity and wisdom, manifested not only to protect their natural environment but also to defend an ancestral heritage. Their cultural heritage, shaped long before the Spanish conquistadors in the 16th century, is a poignant reminder of the need for a respectful balance between the exploitation of natural resources and the preservation of cultures and ecosystems.

These stories, scattered across Latin America, are chapters of the same saga, that of a company confronted with the complex realities of silver extraction, indispensable for the production of silver halide for analog photography. They invite us to deeper reflection on our consumption choices, on the importance of recognizing the origin and impacts of what we often take for granted, and on the necessity to reinfuse spiritual value into matter in a world often dominated by overconsumption and materialism.

Recognizing Temporality in Matter: The Ritual of Analog Photography

In the shadow of environmental and social challenges posed by the mining industry, particularly in the extraction of silver essential for analog photography, emerges a call for deeper consciousness. This call urges us to value and reinterpret our interactions with matter, especially in a world inclined towards overconsumption and materialism. In this context, analog photography becomes a powerful emblem of our connection to time and matter.

In analog photography, each step - loading the film, developing it, and archiving - is more than just a technical process. These gestures, imbued with repetition and precision, are rituals that lend a sacred dimension to the act of photographing. They symbolize a form of resistance to the ephemeral and impersonal nature of the digital age, reminding us of the invaluable worth of every captured moment.

Analog photography then becomes a canvas on which to paint its ideas. Each shot represents a dialectic between light and matter, a tangible manifestation of philosophical concepts such as temporality and eternity. The darkroom, where these images come to life, becomes a sacred space, a laboratory where time is both captured and transcended.

The photographer, in the intimacy of the darkroom, transforms into a true alchemist. Each action, from the exposure of photographic paper to the emergence of the image, is an act laden with meaning, echoing the 'nigredo', the first stage of the alchemical process. In this phase, elements are decomposed and purified, akin to the photographer revealing the hidden image in darkness. It is in this space that analog photography offers a reflective pause, a celebration of the present moment, where each shot becomes a metaphor for alchemical transformation, a journey from darkness to light.

Celebrating Life Through the Lens

Ultimately, the practice of analog photography transcends its initial artistic function. It becomes a meditation on finitude, a celebration of the present moment, and a reflection on our choices and their impacts. In a world dominated by digital, it offers a space for slowness, reflection, and a deeper connection with our material essence. Analog photography, in its ability to capture fragments of time, serves as a poignant testament to the enduring beauty and significance of every fleeting moment, inviting us to embrace the full spectrum of our experiences with mindfulness and reverence.

Comments ()